It often seems as if there is nothing that Israel can do that isn’t disingenuously used to confirm the prejudices of her critics. Whatever the Jewish state does can be marshaled as supposed evidence of her flawed character. But surely the capture of Adolf Eichmann must be considered the exception to that unforgiving rule of international public relations.

As historian Martin Kramer ably writes in this month’s essay, Eichmann’s capture, trial, and execution has become a touchstone of commentary both about how to think about those who perpetrated the Holocaust and about Israel itself. His assessment of the various literary accounts of those who took part in the operation and their subsequent portrayals in film, including the most recent, Operation Finale starring Sir Ben Kingsley as Eichmann, is a convincing and informative guide to the genre. Kramer’s conclusion about the inclination of this latest Eichmann film to humanize the criminal at the center of the story and the need for yet another based on the testimony of Zvi Aharoni to set the historical record straight, is as persuasive as it is authoritative.

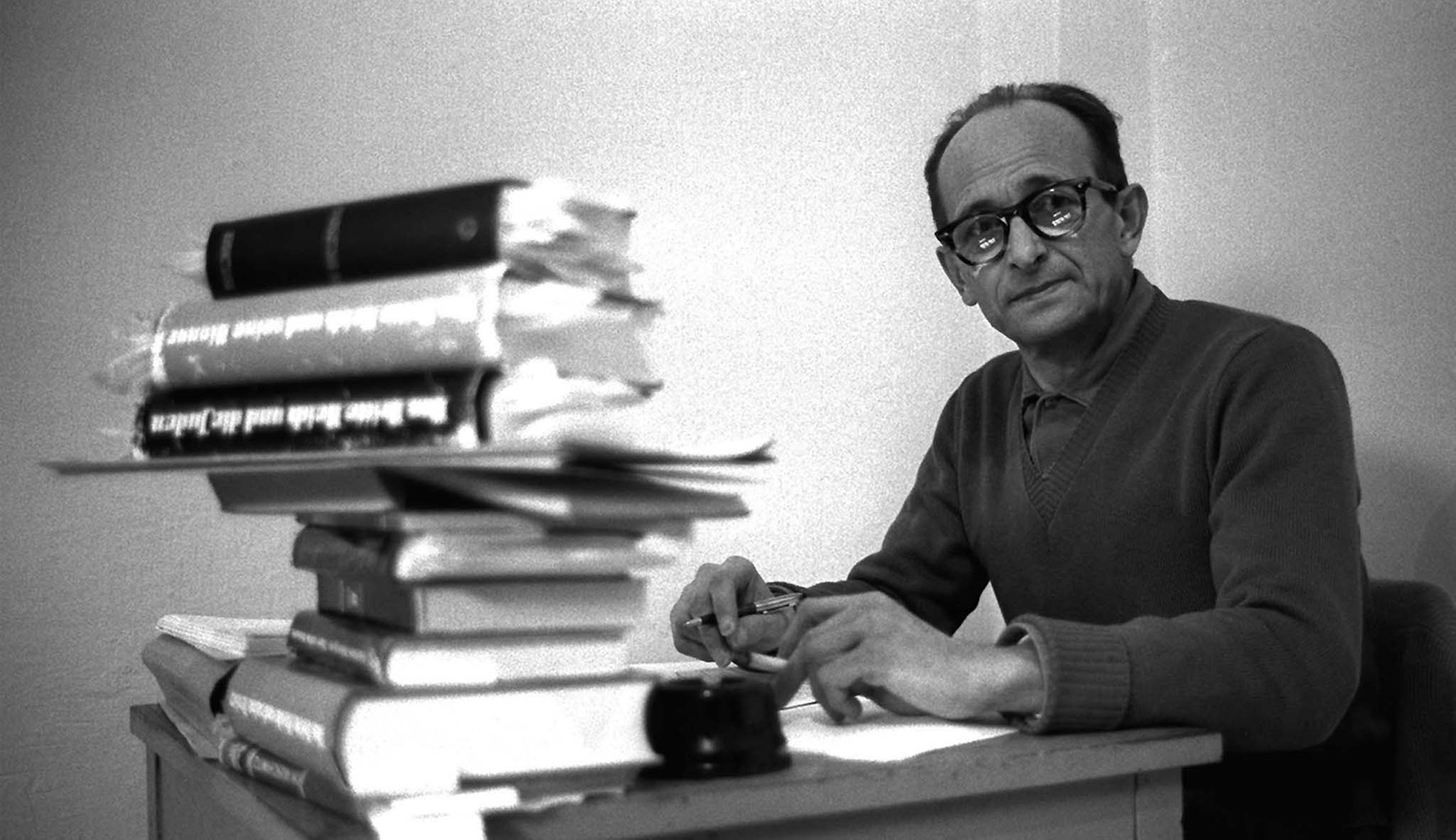

But there is another question to be asked about the seemingly irresistible temptation of those who think, write, and make movies about the Eichmann operation to try to make us view the arch criminal in a nuanced fashion. It is not just that doing so makes Eichmann a more interesting film character than the pitiful human cipher that Mossad chief Isser Harel wrote about in The House on Garibaldi Street or the quintessential embodiment of banality that Hannah Arendt wrote about in her much-debated essays and book about his trial.

The effort to show Eichmann as an affable, sophisticated, and recognizably human mass murderer must also be viewed in the context of the way the world thinks about Israel. Though its creation is linked with the Holocaust in the minds of most observers, Israel is also the only nation-state in the world that is the object of an international campaign to vilify its existence and to wipe it off the map. As such, it is hardly surprising that even discussions about one of its most triumphant moments are bound to be colored by this ongoing struggle.

The debate about other Israeli actions is generally conducted by both opponents and defenders in a manner in which those dedicated to extinguishing the one Jewish state on the planet are shown as ambivalent or even sympathetic characters rather than as soulless killers. So why wouldn’t the same treatment eventually be extended to even a person such as Eichmann, who was hunted down by the same force that now hounds Palestinian and Islamist foes of Israel?

The effort to bring Eichmann to justice in an Israeli court was the first widely reported success of Israel’s now vaunted intelligence services. But it was unlike most of the Mossad and Shin Bet’s subsequent remarkable achievements, which, though admired for their skill, are most often put down as the high-handed actions of a nation with no respect for international norms or the rights of its opponents.

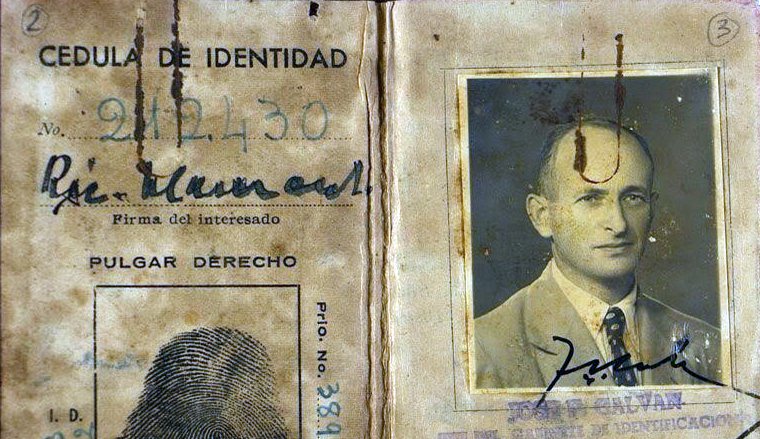

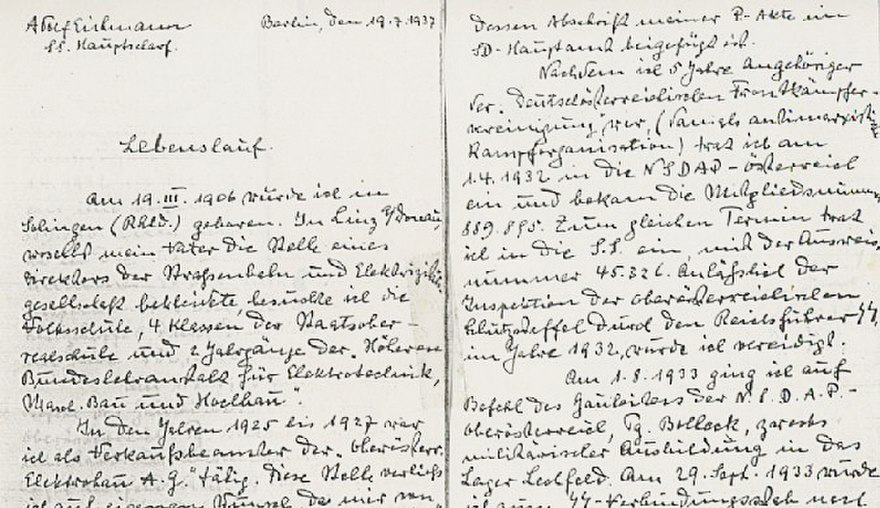

In retrospect, there are few who would quibble with Israel’s riding roughshod over conventional legal procedures in this affair. The tale in which Eichmann was snatched off a street, held in a safe house, coerced into signing a document stating his willingness to be tried in Israel before secretly being flown there, is the stuff of a conventional spy mission. And that is pretty much how Operation Finale comes off, despite its efforts to establish, through Peter Malkin’s personal story, a parallel narrative about Israel’s desire to exact justice for the Holocaust. It is only, as Kramer aptly points out, through the likely fictional dialogue between Malkin, played in the film by Oscar Isaac, and Kingsley’s Eichmann, that the film can be viewed as anything more than just another spy movie in which the prey could be any villain being brought to account for his crimes.

But the need to make Eichmann even more fully realized than the drab little man in the glass booth that we see in the videos of his trial is more than a necessity for a good drama. The sympathetically portrayed Eichmann was, in truth, a dreary bureaucrat, a murderer who translated the Nazis’ belief in the imperative to kill all Jews into action. What explains this transformation? It is a function of the ambivalence about the Jewish exercise of power, even when it is both just and necessary.

Kramer notes Israeli actor Lior Raz’s comments about the story at a showing of the film at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. Raz remarked that his countrymen might have difficulty with the “tenderness” with which Kingsley imbued his portrayal of Eichmann. And, as Kramer points out, the film did not appear in theater there but went instead directly to streaming on the Netflix service.

Raz, who played Isser Harel in Operation Finale, is a minor character in Malkin’s retelling of the story. But his presence in the film reminds us that the television series Fauda that Raz created with journalist Avi Issacharoff touches on similar issues about how we should think about those who seek to murder Jews. Fauda became an international sensation primarily because of its willingness to confront both the moral dilemmas that arise from the necessity of fighting a brutal war as well as its portrayal of the members of Palestinian terrorist groups as recognizably human, with their own sympathetic back stories and families. While the audience is clearly supposed to root for the undercover soldiers led by Raz’s character to prevent their terrorist opponents from slaughtering innocents, those soldiers’ deceptive tactics and their use of violence is also seen as exacting a terrible price on them and the cause of Israel.

While that makes for good television, like the efforts to balance our righteous indignation about Eichmann’s crimes with a tender portrayal of him, it also displays the discomfort Jews themselves have with the use of power. Twenty centuries of exile made Jewish thinkers abhor the force that was so often employed against them. And the legacy of that abhorrence has created a sense in which no action, not even one so obviously necessary as Eichmann’s capture, can be discussed without caveats about the problematic nature of any exercise of authority.

No war, even one that is both necessary and justified, can be successfully fought without doing terrible things. Having been stripped of its underdog status by military victories that ensured its survival, Israel is now judged both harshly and unfairly by a double standard for its measures of self-defense. That has reinforced a reflexive impulse for self-criticism that is given the gloss of moral force by the Jewish tradition’s introspective distaste for surviving by violent means.

Sixty years after the fact, and no matter whose version of the Eichmann capture we are prepared to believe, it is inevitable that any account of the affair, especially those translated into film, will collide with this Jewish ambivalence about the moral price of avoiding further victimhood as well as their internalization of unfair criticisms of Israel.

As we learn from Kramer, unwrapping the various accounts of the Eichmann affair by the Israelis who carried it out is a fascinating exercise for the student of history. Yet all efforts to come to grips with who Eichmann was and why he murdered, as well as how he reacted to the belated justice with which he was served, tell us more about the inner workings of the Jewish psyche than that of an unrepentant Nazi.

So long as Jews struggle with their own complicated feelings about survival in a hostile world, they will always seek to rationalize and humanize their opponents, no matter how ruthless. There are aspects of this trait that are laudable since it helps to place moral limits on the application of lethal force and it allows those who must carry out these grim tasks to maintain their own humanity .

Yet as much as Jews may revel in their quest to understand the foe, the Eichmann story reminds us that there must be limits to the desire to look at murderous anti-Semites as Shakespearian characters who can be admired for their complexity and humanity. Though we seek to understand evil and put it in a context that is recognizably human, Eichmann’s character is fated to always be a mystery that can never be entirely resolved. The only thing to be done with the Eichmanns of this world, who have risen in each generation to plot genocide or to seek to murder the Jews and their state, is to foil their efforts and to bring them to justice. Justice, and not the solipsistic anxieties from which, when confronted with questions of power, Jews continue to suffer, is the only possible moral of any recounting of Eichmann’s capture.

More about: Adolf Eichmann, Eichmann Trial, Israel & Zionism, Mossad