Congratulations and many thanks to Edward Rothstein for “Jerusalem Syndrome at the Met,” his poignant and pungent essay on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Jerusalem 1000–1400: Every People Under Heaven.

The fundamental issue raised by Rothstein—the place in Western museum culture of Jewish history, Jewish ideas, and Jewish art—has quite a long pedigree by now. As my own contribution to this discussion, I’d like briefly here to sketch the relevant background as an aid to understanding where things stand now and where in my view they need to go.

Introducing his landmark volume, Jewish Art: An Illustrated History (1956), the great British historian Cecil Roth opened with a kind of apology: “The conception of Jewish art may appear to some to be a contradiction in terms.” Indeed. An entry in the Jewish Encyclopedia of 1901-5 had gone so far to assert that, when it came to art, Jews were genetically impaired—a defect that, as another entry hopefully proposed, might be remedied by art lessons. Even as late as the 1980’s. I was informed by a professor of art history that there was no such thing as Jewish art, and certainly nothing worthy of study.

In one sense, this adverse judgment was understandable: after all, things “Jewish” were seldom displayed in the finest museums—and when they were, they were often camouflaged. Thus, in one instance, the provenance of a Jewish gold glass from late-antique Rome was given as an “early Christian synagogue”; in another, a 9th-century Islamic hexagram was conspicuously identified as not a star of David. As for explicitly Jewish museums, they, like Roth, were often thrown on the defensive, charged with responding to the widespread idea that any artwork made by or for Jews, if it existed at all, must be inferior.

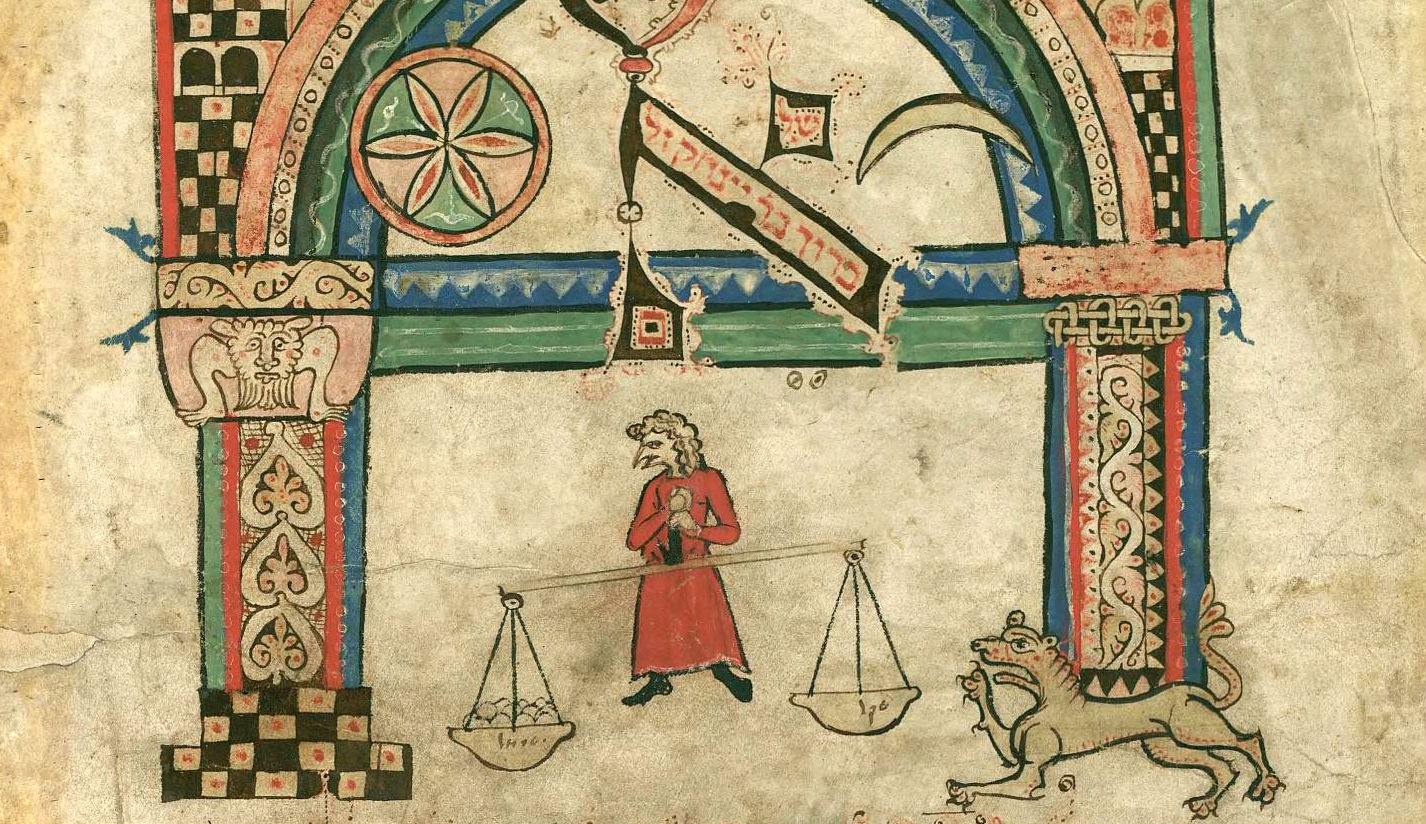

It was not until late in the 2oth century that scholars began to expose the myth of the “artless Jew” (in Kalman Bland’s phrase) and to counter mainstream art historians’ Jewish problem. But cracks in the paradigm had begun to appear much earlier with the publication of medieval illuminated Hebrew manuscripts and the first excavations of ancient synagogues in the Galilee, North Africa, Asia Minor, Syria, and elsewhere. Zionist scholarship played a large role in this development, most visibly through archaeological excavation and the 1906 establishment in Palestine of the Bezalel academy of art, which spawned the Bezalel National Museum, the parent of today’s Israel Museum. The goal of scholars like Rachel Wischnitzer in Berlin (and later New York), Paul Romanoff in New York, and E.L. Sukenik and Mordecai Narkiss in Jerusalem was to exhibit artifacts of such significance as to overpower prejudice.

A single discovery in the Syrian desert in 1932 marked a turning point. This was the magnificent 3rd-century CE synagogue at Dura Europos, with its amazing wall-paintings of biblical scenes from baby Moses in the rushes to the Exodus, from Esther and Mordechai to Ezekiel’s dry bones. Although mainstream scholars still insisted on seeing the find within the framework of preexisting assumptions—as, for instance, the work of Jews who had rejected the supposed anti-aesthetic strictures of the ancient rabbis—others, like Sukenik, quickly understood it for what it was.

Most prominent among this latter group was Kurt Weitzmann (1904-1993), who as a graduate student in Berlin during Hitler’s rise to power had become enthralled with the Dura frescoes. Unemployable in Germany without submitting to Nazification, Weitzmann left for the United States and a position at Princeton, where he and successive generations of his students convincingly placed the Dura paintings within a lost tradition of Jewish illuminated Septuagint manuscripts, precursors of Christian art and central monuments in the history of Western art.

But there was more to it than that, and the “more” ties into our current situation. Weitzmann saw Dura Europos, a border city containing all sorts of Roman-era religious buildings—including the synagogue and the earliest church yet uncovered—as a kind of multicultural oasis and model of coexistence. In his vision, Dura represented an uncanny harbinger of interwar Berlin and postwar New York: a lost paradise, wished for and imagined by an exiled German scholar in search of a better world.

In 1979, Weitzmann’s vision found expression in his monumental Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition, The Age of Spirituality: Late Antique and Early Christian Art, Third to Seventh Century. Smoothly divided into five sections—“The Imperial Realm,” “The Classical Realm,” “The Secular Realm,” “The Jewish Realm,” and finally “The Christian Realm”—the show made no mention of the less happy side of late-antique “spirituality,” eliding the catastrophe that was already being visited upon “polytheistic,” Jewish, and non-Orthodox Christian culture by a Christianized empire. As the Yale scholar Margaret Olin has shown, Weitzmann’s approach was not mere academic blindness but likely intentionally prescriptive. That being so, it was no accident that The Age of Spirituality presented an undisturbed “Jewish Realm,” or that this section of the exhibition should have been curated by the Israeli art historian Bezalel Narkiss, a Weitzmann acolyte and the son of Mordecai Narkiss.

The Age of Spirituality was the first major American exhibition frontally to engage Jewish visual culture, and its theme of cultures “getting along” soon became quite common. Milestones included Precious Legacy: Judaic Treasures from Czechoslovak State Collections (1983), which was produced by the Smithsonian and traveled to ten cities across the U.S., and two exhibitions by the Jewish Museum in New York: Gardens and Ghettos: The Art of Jewish Life in Italy (1990) and Convivencia: Jews, Muslims, and Christians in Medieval Spain (1992). Smaller museums across the country followed suit. My own Sacred Realm: The Emergence of the Synagogue in the Ancient World (Yeshiva University Museum, 1996), itself consciously modeled on The Age of Spirituality, was part of this trend, tracing the origins of both church and mosque to the ancient synagogue without a hint of the well-documented destruction of synagogues (not to mention Roman temples and cult sites) by the newly Christian empire of the 5th-7th centuries.

These exhibitions were not alone in focusing upon the “happy” in Jewish experience. In the second half of the 20th century—in spite of, or in response to, the always hovering shadow of the Holocaust—major historians of Judaism, especially Cecil Roth (Oxford) and Salo Wittmayer Baron (Columbia), similarly under-acknowledged the real complexities of the pre-modern Jewish experience in Europe, in an attempt to provide educated, Westernizing Jews with a positive history they could embrace and be proud of: the same positive impulse that informed art exhibitions from the The Age of Spirituality to Sacred Realm.

The problem is that the model was overwrought.

Museum exhibition has never been strictly “academic.” It is a form of public education, and museum scripts, design decisions, and the artifacts chosen for display always provide conceptual frameworks for navigating both the past and the present. In this light, it is not surprising that, a decade after 9/11, three exhibitions dealing with interreligious and interethnic relations in the eastern Mediterranean appeared almost simultaneously at New York institutions: Edge of Empires: Pagans, Jews, and Christians at Roman Dura Europos (Institute for the Study of the Ancient World), Transition to Christianity: The Art of Late Antiquity, 3rd-7th Century AD (Onassis Center), and the most prominent of the three, Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition at the Met.

For the last-named of these, I helped to choose the Jewish artifacts and contributed an article on “Jews and Judaism under Byzantium and Islam” to the catalog. As I wrote shortly afterward, all three shows intentionally modeled a world of commonality that we would most like to see and to believe once existed, thereby refuting the notion of an inevitable “conflict of civilizations” that had become a staple of American political discourse after 9/11. In aid of this goal, each reconfigured history. The Dura exhibition presented a kind of ancient convivencia, playing down the fact that the city was destroyed by Persian invaders in 256 CE. Transition to Christianity, for its part, elided the fact that imperial Christianity destroyed or subjugated all other religions in its wake, and Byzantium and Islam underestimated the power differential between the conquered Byzantines and Islam triumphant.

Jerusalem 1000–1400: Every People Under Heaven fits well within this larger pattern. If, not so long ago, the mere inclusion of Jewish artifacts would have been unheard of in a museum exhibition, now Jewish materials are placed near center stage—but they are still not at home, being made to fit contemporary visions and interests in a way that scants or denies the complexity that they actually express.

There is no reason why our great American museums cannot do better. To their credit, institutions from the Met in New York to the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore to Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts and especially the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh have made serious attempts to highlight and expand their Judaica holdings, and to integrate the Jewish experience within the larger story of art. This is real progress, but there is more work, especially of a conceptual kind, to be done.

And Jewish museums can do better as well. In North America, Europe, and especially in Israel these venues have an essential role to play as public interpreters of Jewish history and Jewish culture. Unfortunately, some major American Judaica museums have veered far both from Jewish content and from the fruits of Jewish scholarship. The past is just too interesting, and the future too important, for such modishness to prevail.

Two journals, the Israeli Ars Judaica and my own Images: A Journal of Jewish Art and Visual Culture, provide academic underpinnings for exploring the full tactile side of Jewish history and for revealing the sweep and the depth of a magnificent and astonishingly evocative visual culture. It is time to move beyond The Age of Spirituality and Jerusalem 1000–1400, and everything in-between. Hearty thanks again to Edward Rothstein for airing the relevant issues and for pushing them to the forefront of public conversation.

More about: Arts & Culture, History & Ideas, Jewish museums