Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].

Among the many things said about President Barack Obama in Ally, the new book by Israel’s ex-ambassador to the U.S. Michael Oren, there is one that few readers may have paused to reflect on. Yet in reading Ally, I couldn’t help wondering about the assertion, made midway through Oren’s controversial analysis of Obama’s character as a product of childhood experience, that the president’s “pervasive belief in the power of words . . . reminded me of the ancient Aramaic incantation ‘Abracadabra,’ meaning ‘I speak therefore I create.’”

For a moment, forgetting all about AIPAC, Iran, and the state of Israeli-American relations, I found myself asking: is abracadabra, one of the few five-syllable English words probably known to every five-year-old speaker of the language, really Aramaic in origin? And if it is, does it mean what Michael Oren says it does?

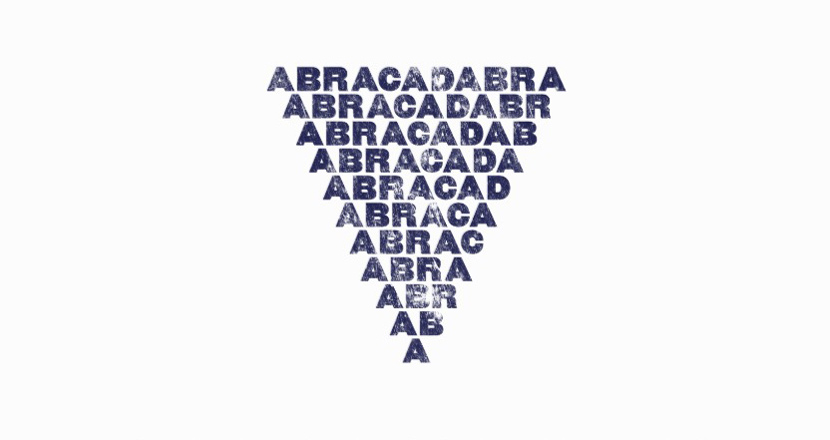

It’s a word, it turns out, with a long written history. The earliest reference to it occurs in a Latin text, Serenus Sammonicus’ De Medica Praecepta. Serenus was the physician of the Roman emperor Caracalla, who reigned from 188 to 217 CE, and in treating of fevers and colds he prescribes an amulet on which is written:

ABRACADABRA

ABRACADABR

ABRACADAB

ABRACADA

ABRACAD

ABRACA

ABRAC

ABRA

ABR

AB

A

This amulet, writes Serenus, should be worn around the neck for nine days. On the morning of the tenth day, the patient should rise before dawn and discard the amulet in a flowing river, whereupon he or she will be cured.

How many fevers or colds were gotten over in this way, I don’t know. Yet the magical logic of the treatment seems clear. As the eleven letters of abracadabra diminish day by day, so does the power of the illness until, by Day Ten, when only one letter is left, it has been weakened enough to be cast off.

Medical spells of this sort were common in antiquity and were practiced by Jews as well as Gentiles. The Babylonian Talmud speaks of a condition known in Aramaic as shabrirey, a temporary attack of blindness brought about by contact with an aquatic demon named Shabrir. This was treated, according to the tractate Avodah Zarah, by means of the incantation shabrirey, brirey, rirey, irey, rey, which gradually shank the demon’s hold on the blinded person. “Abracadabra” was no doubt such a charm, too.

But if the ancient purpose of the word seems clear, its origins are anything but. “I speak, therefore I create” is Oren’s version of a hypothetical Hebrew (not Aramaic) phrase suggested by others before him: evra k’divra,“I create as is the spoken word”—an implied comparison of the healer’s magical powers with those of the biblical God who created the world by speech alone. Not only, however, is such a phrase unknown to rabbinic or other Jewish tradition (from which it supposedly was absorbed, perhaps via Jewish Gnostic circles, into Graeco-Roman culture), it makes no sense in terms of the gradual diminution of the letters on the amulet. Why would the healer want to diminish his own powers?

Numerous other explanations of abracadabra have been given, none of them any more convincing. Its source has been proposed as Aramaic avad k’davra, “it has perished like the plague.” (Alas, though this interpretation provides the “killing curse” of Avada Kedavra in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series, no Aramaic word davra corresponding to Hebrew dever, “plague,” exists.) As the invention of Jewish Christians, abra being an acronym of Hebrew av, ben, and ruaḥ ha-kodesh, “father,” “son,” and “holy spirit,” and kadabra of ha-kadosh barukh hu, “the Holy One Blessed Be He.” (This strikes one as far-fetched—and, once again, why the diminution?) As Abrasax or Abraxas, the supreme archon or ruler of this world, considered an evil demiurge in certain forms of Gnosticism. (This name is indeed found on many ancient amulets, but how did its ending change from “sax” or “xas” to “cadabra?”) As a nonsense word formed from “a,” “b,” “c,” and “d,” the first four letters of the Latin alphabet. (How, though, unless we are dealing with an ancient placebo, would a nonsense word have affected a demon?) And on and on.

One of the more recent ideas concerning abracadabra’s reputed Jewish provenance comes from the late Amram Kehati, an Israeli student of Jewish mysticism who argues that the word is a garbling of Hebrew ארבע-אחד-ארבע, arba-eḥad-arba or “four-one-four.” As far as I can follow Kehati’s reasoning, it’s that ancient Hebrew or Aramaic magic spells against demons must have consisted of nine rather than eleven characters, nine being a symbol of evil in the Jewish numerology of the age, and that the demon’s name was shrunk by progressively removing the letters on either side of the middle one until that alone remained; arba-eḥad-arba, its ḥet pronounced by the gutturally-challenged Romans as a hard “c,” would thus have been a generic term for all such spells, not a proper name in one of them. Yet while it’s a nice theory, there’s no external evidence to back it up. On the contrary: shabrirey (שברירי), the only example of such a Hebrew/Aramaic spell that we have from talmudic times, has six letters, not nine.

Where does abracadabra come from? It’s anyone’s guess. When, in the first of 125 separately published fascicules that eventually comprised the entire work, the Oxford English Dictionary said of it “origin unknown,” the date was 1884. Nothing much has changed since.

Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].

More about: Aramaic, Hebrew, History & Ideas, Magic